CURATION

- from this page: by Matrix

Network Node

- Name: Seckou Keita

- City/Place: Sneiton

- Country: United Kingdom

- Hometown: Ziguinchor, Senegal

Life & Work

-

Bio:

by Andy Morgan

When Seckou Keita came to the UK in the late 1990s at the tender age of 21, he had only left his native Senegal twice before (to play in Norway and India). He spoke little English, was neither famous (yet) nor particularly experienced. Twenty years later, Seckou was named BBC Radio 2 Folk Musician of the Year, a startling choice for such a blue-blooded British institution. “For me, it was an amazing kind of recognition, for my participation in the British music scene starting with Baka Beyond, all the folk people I worked with years back…until I reached a new level with Omar Sosa, with my own solo music, with AKA Trio, with Catrin Finch and the Lost Words Project. And then suddenly it was like ‘Oh!’”.

In that one exclamatory ‘Oh!’ lies all the joy, surprise and relief of a man who sets out on a long journey, with no map, compass or even destination to speak of, and then realises one fine day that he has arrived. Not even the most skilled clairvoyant in Seckou’s home region of Casamance in southern Senegal, could have foretold such a journey. A life in music, yes: Seckou was born into a family of griots or hereditary bards, so that was entirely predictable. But a life in music that widened the horizons of the kora, involved collaborations with leading musicians of every stripe and earned the love and respect of audiences all over the world, all that could hardly have been imagined.

Seckou was born in Ziguinchor, capital of the Casamance region, in 1978. His family was presided over by the patriarchal figure of his grandfather Jali Kemo Cissokho, one of the most revered griots in that part of West Africa (‘jali’ is the Mandinka word for ‘griot’). Music had been the family business for at least three centuries, probably much longer, and all Seckou’s uncles and grand uncles on his mother’s side were virtuosi of the kora, the griot’s instrument of choice. His father, a roving holy man by the name of Elhaji Mohammed Keita was descended from the great Sunjata Keita, founder of the medieval Malian Empire. Elhaji Mohammed disappeared from Seckou’s life when he was still a baby and became, as far as Seckou was concerned, ‘the invisible man’.

Jali Kemo was a hard taskmaster. From the age of seven, Seckou, whose nickname was Jali N’ding (the little griot), had to get used to pre-dawn awakenings, Quranic school and endless practice on the kora. “It was like a 13th century way of raising a child brought into the 20th century,” Seckou says. As he grew older and began to take an interest in drums and other forms of music beyond the traditional repertoire, Seckou even felt picked-on by his grandfather, who often singled him out for the harshest treatment. Only later, with the onset of wisdom, did he realise how important the discipline, work and self-respect his grandfather instilled would be for his future success.

Having mastered the seourouba, sabar and djembe drums, Seckou became jali dundun, the ‘griot drummer’, playing throughout the region with his own band or accompanying his grandfather and uncles to various celebrations and feasts. At the age of fifteen, he travelled to the capital Dakar to play some concerts with his uncle Jali Solo Cissokho, who had recently released two hit cassettes. Three years later, Seckou was given his first kora, a gift that marked the end of his apprenticeship and the beginning of his own mission to ‘globalise’ the kora, taking it out of its hereditary African context and cross-fertilising it with the music of other worlds.

In 1996, Seckou and his uncle Sadio Cissokho were invited to take part in a collaborative project with musicians from Cuba and India at the Riksscenen in Oslo, Norway. “I had all my imagination as a child about what Europe was like,” he remembers. “And when I got there it was shocking. What I had imagined, I didn’t find. What was in my nature, I didn’t see either. So I was lost for a bit.” The trip to Norway led to an invitation by the violinist and composer Dr L. Subramaniam to do a series of concerts in India. Shortly afterwards he returned to Norway and paid his first visit to England at the invitation of some music students he’d met in Senegal.

Seckou’s innate ability to charm, adapt and learn fast enabled him to thrive in a cold and alien climate. He began by touring schools and universities with a company called Dadadrum and went on to work with the Sierra Leonean Francis Fuster, Baka Beyond, Peter Badejo’s African dance company Badejo Arts, the Welsh harpist Llio Rhydderch and the folk musician Martin Simpson. He played in the London production of The Lion King and helped to set up the very first Kora Exam course at the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) in London.

He released his first solo kora album Baiyo (Orphan) in 2000 (its name was later changed to Mali) and began to develop new tunings for the instrument, often stumbling across by mistake. “My tunings became my signatures,” he says. He supported Youssou N’Dour and Salif Keita and became a regular fixture on the international WOMAD festival circuit, performing in Singapore, Australia, UK and the Canary Islands. In 2003, he founded a band called Jali Kunda, comprising members of his family, and released an album called Lindiane after the suburb of Ziguinchor where he grew up.

Seckou formed his own band, the Seckou Keita Quartet, with Gambian ritti player Juldeh Camara, bassist Davidé Mantonvani and Seckou’s brother Surahata Susso (Juldeh was later replaced by the violinist Samy Bishai). In 2006, the group released Tama Silo: Afro Mandinka Soul, and Seckou took them back to Senegal to show his family what the wayward ‘little griot’ had achieved. For the next album Silimbo Passage (2008) and the 400 gigs that followed in its wake, with sold out shows in Europe, Australia, New Zealand, USA, Canada, Asia, SKQ were joined by Seckou’s sister Binta Suso. Fifty percent of album revenue was donated to the International Committee of the Red Cross, an organisation that had found a place close to Seckou’s heart ever since the Casamance separatist struggle of the 1980s, during which he experienced the suffering of war firsthand. In parallel (Seckou seems to a consummate plate spinner), Seckou released Live at Couleur Café (2005) with Mamady Keita, the greatest living djembe player, and later teamed up with Doug Manuel, founder of Sewabeats, and Philippe Fournier, founder of the Lyon Symphony Orchestra, in the hugely successful percussion extravaganza Do You Speak Djembe?

In 2012, Seckou released his album Miro on Astar Music. It hit the No. 1 slot in the European World Music charts and lead to a European tour with a twelve-piece band. Later that year, Seckou was giving a concert to a UN Delegation in Rome when he received a call from his manager. The kora maestro Toumani Diabate by been held up by political turmoil in Mali and couldn’t make rehearsals for a forthcoming tour with the Welsh classical harp virtuoso Catrin Finch. Could he be the last-minute stand in? Seckou, always primed for new adventures, said yes. Catrin Finch and Seckou Keita became one of the most successful cross-cultural collaborations of recent years, and the most perfect realisation of Seckou’s mission to keep the kora truly alive, fluid and changeable, like a living thing, always ready to travel and breed with other styles.

The pair’s debut release Clychau Dibon (2013) won Songlines Best Cross-Cultural Collaboration (2014), fRoots Critics Poll Album of the Year (2013). The follow up album Soar (2018), inspired by the wondrous migrations of the osprey, reaped another harvest of awards: Songlines Best Fusion Album (2019), fRoots Critics Album of the Year (2018), Trans-regional Album of Year in the Transglobal World Music Charts (2018), Best Duo/Band at the BBC Radio 2 Folk Awards, Top Ten Album in Mojo magazine. Seckou and Catrin were under pressure to deliver the ‘difficult second album’ following the immense success of the first. “It was a challenge,” he says. “Because the first album had a big echo. People loved it. And with the second we had to match it or go beyond.” Which is precisely what happened.

Between the two albums, Seckou released his solo opus 22 Strings (2015), a very personal expression of attachment to his homeland, his absent father and to the kora itself, its grandeur and stillness. “I wanted to deliver something from my heart to other hearts,” he says. “I wanted to bring the kora back to its own land, where it really belongs.” The album earned Seckou a Songlines Best Album - Africa & Middle East Award.

Back in 2012, Seckou was introduced to the Cuban composer and pianist Omar Sosa by the drummer Marque Gilmore. “We didn’t have much to say to each other at first,” Seckou says, “but then we started getting to a kind of high level of musical spirituality. I love that with him. I just connected.” The release of their debut album Transparent Water was held up by bursting schedules and other commitments, but its reception in 2017 was more than enthusiastic. The duo ended up doing more than a hundred shows with the Venezuelan Gustavo Ovalles on percussion, in the USA, Asia, Japan, Europe and South America.

In 2016, Seckou was invited by Africa Express to take part in a European tour with the Orchestra of Syrian Musicians and an all-star host of guests. At show in London and Amsterdam, Seckou accompanied Paul Weller and the Syrian orchestra in a supernational version of ‘Wildwood’, his kora sprinkling Weller’s very English soulfulness with African grace.

And if all that wasn’t enough, Seckou managed to crowbar more time out of his busy schedule for another project: AKA Trio. He first performed with Italian guitarist Antonio Forcione and Brazilian percussionist Adriano Adewale Ikauna at the Edinburgh Festival in 2011. “It was powerful,” Seckou remembers. “Ideal musicians, ideal talent.” But once again, life intervened to postpone the trio’s debut album until 2019. Entitled Joy, it enjoyed good reviews and was accompanied by a successful UK tour. “It was a dream come true,” Seckou says.

Also somehow crowbarred in was Music Book: a compendium of Kora music scores for piano, cello, violin, flute and clarinet. With every passing year, Seckou was acutely aware that the centuries-old oral transmission of the griot’s art, from one Cissokho generation to the next, might end with him. Unlike his grandfather Jali Kemo, he didn’t have all the time in the world to bequeath his ancient knowledge to his children and grandchildren. So, he teamed up with jazz musician and producer Alex Wilson to embark on the painstaking job of transcribing a set of his own pieces into musical notation. “I wanted to create something that my kids, and other kids would be able to grab and learn,” he says. “It was an amazing achievement. It means my music will probably live longer than me.”

In 2018, Seckou was asked to join a top-ranking slate of UK folk musicians, including Karine Polwart, Julie Fowlis, Kris Drever from Lau, Kerry Andrew, Rachel Newton, Beth Porter and Jim Molyneau to record The Lost Words: Spell Songs, a musical adaptation of the (quite literally) magical book The Lost Words by Robert MacFarlane with dazzling illustrations by Jackie Morris. In the book’s inspired attempt to recover words that are being lost due to the rapid urbanisation of human existence – words like ‘heather’, ‘fern’, ‘heron’, ‘kingfisher’, ‘raven’ – Seckou discovered many intriguing parallels with Africa. “I was totally inspired by the book, realising that back home, words get lost because some languages are dominated by other more powerful ones.” Griots are the traditional conservators of music, words and stories, so ideals behind The Lost Words already flowed in Seckou’s veins.

Seckou’s frenzy of creativity and work was guillotined by Covid 19 at the start of 2020, just after sold out shows with Catrin Finch at the Sydney Opera House and the WOMAD festivals in Australia and New Zealand. Lockdown was bad, but it wasn’t all bad. “It gave you a chance to think,” he says. “It was like a university of seeing the world in a different way. We’ve become so good at doing doing doing that we’ve forgotten how to be. And I think the pandemic taught us a bit how to be.” A total stoppage was out of the question and in February 2020, Seckou released a song called ‘Am Am’, which means ‘wealth’ or ‘prosperity’, a meditation on how fortunes can be won then lost in an instant thanks to marital breakdown or some other crisis. The accompanying video became a hit on Trace TV, a French music channel popular in West Africa.

To record his next single ‘Now or Never’, Seckou gathered together, digitally speaking, a band of friends and fellow travellers from all corners of the earth and every chapter of his own story. They included Fatoumata Diawara (Mali), Noura Mint Seymali (Mauretania), Manecas Costa (Guinea Bissau), Anandi (India), Zule Guerra (Cuba), Kris Drever (Scotland), Celestine Walcott-Gordon (UK/Barbados), Keyti (Senegal), Mustapha Gueye (Senegal), Mieke Miyazaki (Japan) and producer Hakim Abdul Samad (USA). The song was a reflection on the necessity of finding solutions to some of humanity’s deepest problems in the post-Covid world. As a griot, he felt he was under an obligation to act, to help. “The pandemic is a sign,” he says. “Black Lives Matter is another sign. So, what’s next? There’s only cure: coming together.” In late 2020, Seckou contributed kora to the song ‘Rockets’, written by Paul Weller and released on his album On Sunset.

Both projects were part of a very tentative and gradual return to Africa for Seckou. “I need Africa and Africa needs me,” Seckou says, qualifying this by adding “I’d like to communicate my experience to the younger generation.” Seckou has been releasing a single a year in his home country for a while now, and marvels at the living that artist can make in Africa by releasing regular singles (no albums) with an accompanying video and reaping rewards from YouTube revenue and concert ticket sales. “More and more, I think that’ll be my way of doing things,” he says.

As soon as the virus permits, Seckou is primed and loaded for further adventures. In February 2021 he releases a new song called ‘Elles Sont Toutes Belles’, featuring the Kora Award winning singer and leading Senegalese gawlo[1] artist Aïda Samb. A new album with Omar Sosa is mixed and ready for release. He starts recording a new Catrin Finch and Seckou Keita album with the Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra, a dream of long standing and a good fit with the overall mission to “extend the framework of the kora.” There’s another Lost Words album project pencilled in for 2021. More singles for the African market (and hopefully others), collaborations with Senegalese artists, including Baaba Maal, with whom he just finished recording a song called ‘Homeland’. “That’s where my focus is at the moment, because I’ve collaborated a lot in the West, but not enough in the land of Africa in general.”

Every arrival must be followed by a departure, so the journey continues, destination unknown.

Contact Information

- Email: [email protected]

-

Management/Booking:

BOOKING

[email protected]

MEDIA & PR

[email protected]

PR for Homeland, Seckou Keita feat. Baaba Maal

[email protected]

Media | Markets

- ▶ Buy My Music: http://www.seckoukeita.com/shop-1

- ▶ Buy My Vinyl: http://www.seckoukeita.com/shop-1

- ▶ Book Purchases: http://www.seckoukeita.com/shop-1

- ▶ Twitter: seckoukeita

- ▶ Instagram: seckoukeitamusic

- ▶ Website: http://www.seckoukeita.com

- ▶ YouTube Channel: http://www.youtube.com/c/seckoukeitaofficial

- ▶ YouTube Music: http://music.youtube.com/channel/UCXZuwtooaT4CeuaoPdLOXMw

- ▶ Spotify: http://open.spotify.com/album/1VH0jLzs9p6WzXRlfRk7Hw

- ▶ Spotify 2: http://open.spotify.com/album/05zAa96vJNiqrT9GBc6n3O

- ▶ Spotify 3: http://open.spotify.com/album/45qiD0VlL8yvLprYTsIsXK

- ▶ Spotify 4: http://open.spotify.com/album/6sMLaItoTxTwETaIPYrEiv

- ▶ Spotify 5: http://open.spotify.com/album/4EYDGs1XVGoNaL9vSA246G

- ▶ Spotify 6: http://open.spotify.com/album/0ELSoNJWrenXxTTuykSmp3

Clips (more may be added)

-

OMAR SOSA & SECKOU KEITA - KHARIT

410 views

-

Seckou Keita - Kanou

379 views

-

Seckou Keita - Mikhi Nathan Mu Toma (The Invisible Man - Official Video)

293 views

The Matrix is a small world network. Like stars coalescing into a galaxy, creators in the Matrix mathematically gravitate to proximity to all other creators in the Matrix, no matter how far apart in location, fame or society. This gravity is called "the small world phenomenon". Human society is a small world network, wherein over 8 billion human beings average 6 or fewer steps apart. Our brains contain small world networks...

![]() Wolfram MathWorld on the Small World Phenomenon

Wolfram MathWorld on the Small World Phenomenon

![]() Matemática Wolfram sobre o Fenômeno Mundo Pequeno

Matemática Wolfram sobre o Fenômeno Mundo Pequeno

"In a small world, great things are possible."

It's not which pill you take, it's which pathways you take. Pathways originating in the sprawling cultural matrix of Brazil: Indigenous, African, Sephardic and then Ashkenazic, European, Asian... Matrix Ground Zero is the Recôncavo, contouring the Bay of All Saints, earthly center of gravity for the disembarkation of enslaved human beings — and the sublimity they created — presided over by the ineffable Black Rome of Brazil: Salvador da Bahia.

("Black Rome" is an appellation per Caetano Veloso, son of the Recôncavo, via Mãe Aninha of Ilê Axé Opô Afonjá.)

"Dear Sparrow: I am thrilled to receive your email! Thank you for including me in this wonderful matrix."

—Susan Rogers: Personal recording engineer for Prince, inc. "Purple Rain", "Sign o' the Times", "Around the World in a Day"... Director of the Berklee Music Perception and Cognition Laboratory

"Thanks! It looks great!....I didn't write 'Cantaloupe Island' though...Herbie Hancock did! Great Page though, well done! best, Randy"

"We appreciate you including Kamasi in the matrix, Sparrow."

—Banch Abegaze: manager, Kamasi Washington

"This is super impressive work ! Congratulations ! Thanks for including me :)))"

—Clarice Assad: Pianist and composer with works performed by Yo Yo Ma and orchestras around the world

"Dear Sparrow, Many thanks for this – I am touched!"

—Julian Lloyd-Webber: UK's premier cellist; brother of Andrew Lloyd Webber (Evita, Jesus Christ Superstar, Cats, Phantom of the Opera...)

"Thanks, this is a brilliant idea!!"

—Alicia Svigals: World's premier klezmer violinist

Developed here in the Historic Center of Salvador da Bahia ↓ .

![]() Bule Bule (Assis Valente)

Bule Bule (Assis Valente)

"♫ The time has come for these bronzed people to show their value..."

Production: Betão Aguiar

MATRIX MODUS OPERANDI

Recommend somebody and you will appear on that person's page. Somebody recommends you and they will appear on your page.

Both pulled by the inexorable mathematical gravity of the small world phenomenon to within range of everybody inside.

And by logical extension, to within range of all humanity outside as well.

MATRIX (PARDAL)

I'm Pardal here in Brazil (that's "Sparrow" in English). The deep roots of this project are in Manhattan, where Allen Klein (managed the Beatles and The Rolling Stones) called me about royalties for the estate of Sam Cooke... where Jerry Ragovoy (co-wrote Time is On My Side, sung by the Stones; Piece of My Heart, Janis Joplin of course; and Pata Pata, sung by the great Miriam Makeba) called me looking for unpaid royalties... where I did contract and licensing for Carlinhos Brown's participation on Bahia Black with Wayne Shorter and Herbie Hancock...

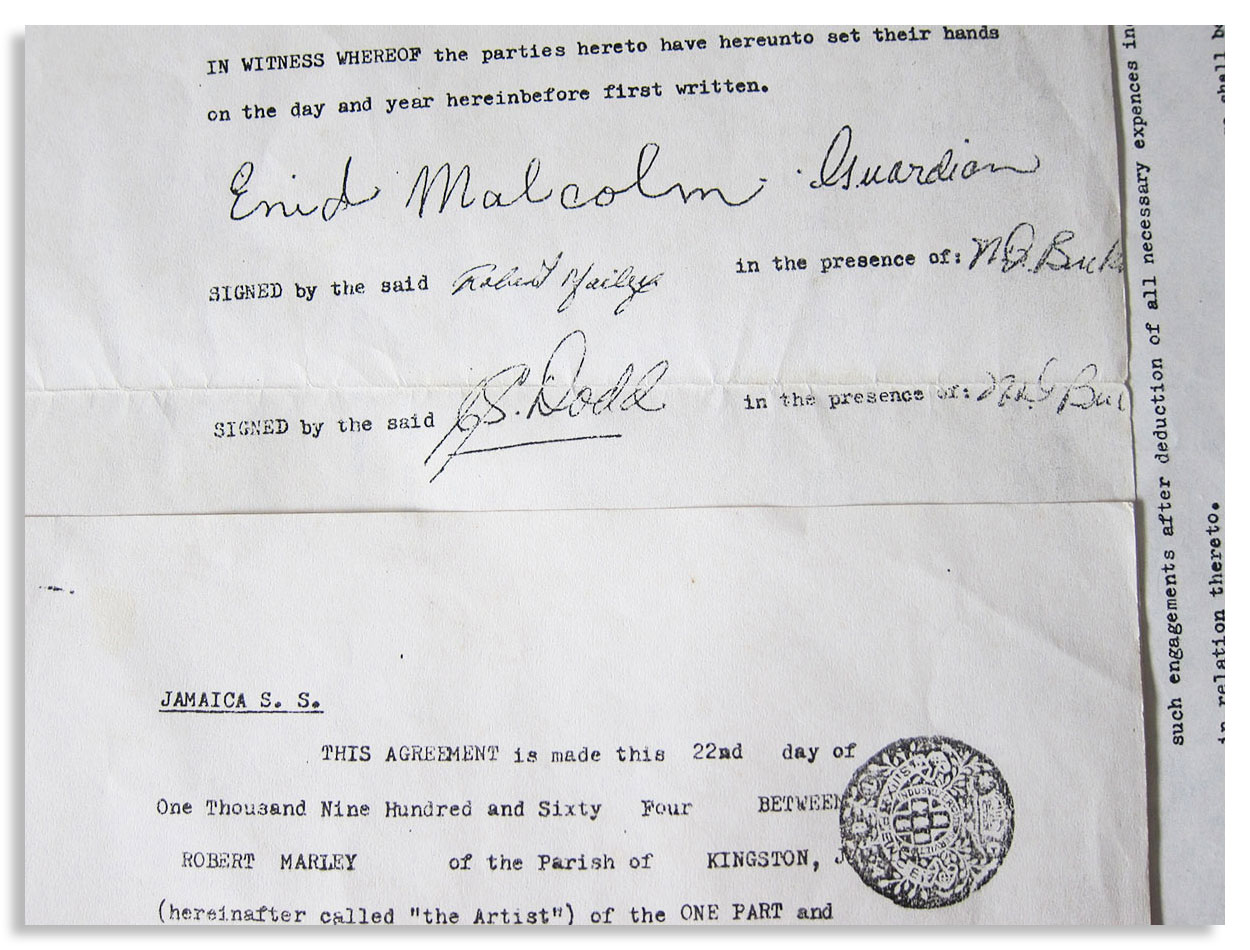

...where I rescued unpaid royalties for Aretha Franklin (from Atlantic Records), Barbra Streisand (from CBS Records), Led Zeppelin, Mongo Santamaria, Gilberto Gil, Astrud Gilberto, Airto Moreira, Jim Hall, Wah Wah Watson (Melvin Ragin), Ray Barretto, Philip Glass, Clement "Sir Coxsone" Dodd for his interest in Bob Marley compositions, Cat Stevens/Yusuf Islam and others...

...where I worked with Earl "Speedo" Carroll of the Cadillacs (who went from doo-wopping as a kid on Harlem streetcorners to top of the charts to working as a janitor at P.S. 87 in Manhattan without ever losing what it was that made him special in the first place), and with Jake and Zeke Carey of The Flamingos (I Only Have Eyes for You)... stuff like that.

Yeah this is Bob's first record contract, made with Clement "Sir Coxsone" Dodd of Studio One and co-signed by his aunt because he was under 21. I took it to Black Rock to argue with CBS' lawyers about the royalties they didn't want to pay (they paid).

MATRIX MUSICAL

I built the Matrix below (I'm below left, with David Dye & Kim Junod for U.S. National Public Radio) among some of the world's most powerfully moving music, some of it made by people barely known beyond village borders. Or in the case of Sodré, his anthem A MASSA — a paean to Brazil's poor ("our pain is the pain of a timid boy, a calf stepped on...") — having blasted from every radio between the Amazon and Brazil's industrial south, before he was silenced. The Matrix started with Sodré, with João do Boi, with Roberto Mendes, with Bule Bule, with Roque Ferreira... music rooted in the sugarcane plantations of Bahia. Hence our logo (a cane cutter).

A Massa (do povo carente) / The Masses (of people in need)

-

Add to my PlaylistA Massa - Raymundo Sodré (7,093 plays)

-

Add to my PlaylistSina de Cantador - Raymundo So... (6,909 plays)

-

Add to my PlaylistMagnetismo - Raymundo Sodré ... (6,353 plays)

-

Add to my PlaylistSacando a Cana - Raymundo Sodr... (5,957 plays)

-

Add to my PlaylistMêrêrê - Raymundo Sodré (5,465 plays)

-

Add to my PlaylistJardim do Amor - Raymundo Sodr... (4,677 plays)

-

Add to my PlaylistDebaixo do Céu - Raymundo Sodr... (4,151 plays)

-

Add to my PlaylistDesejo de Amar - Raymundo Sodr... (3,861 plays)

-

Add to my PlaylistOração pra Yá Oxum - Raymundo ... (3,741 plays)

-

Add to my PlaylistYá África - Raymundo Sodré (3,509 plays)

-

Add to my PlaylistMeu Rio, Cadê o Papel - Raymun... (3,177 plays)

-

Add to my PlaylistCasa de Trois - Raymundo Sodré... (2,896 plays)

-

Add to my PlaylistMulher é Laço que Prende o Coração do Vaqueiro - R... (2,556 plays)