CURATION

- from this page: by Augmented Matrix

Network Node

- Name: Steve Earle

- City/Place: New York City

- Country: United States

- Hometown: San Antonio, Texas

Life & Work

-

Bio:

When asked about what drove him to craft his deeply evocative new album, Ghosts of West Virginia, Steve Earle says that he was interested in exploring a new approach to his songwriting. “I’ve already made the preaching-to-the-choir album,” he says, specifically alluding to his 2004 album, The Revolution Starts Now. As anyone as politically attuned as Earle understands, there are times when the faithful need music that will raise their spirits and toughen their resolve. But he came to believe that our times might also benefit from something that addresses a different audience, songs written from a point of view that he is particularly capable of rendering.

“I thought that, given the way things are now, it was maybe my responsibility to make a record that spoke to and for people who didn’t vote the way that I did,” he says. “One of the dangers that we’re in is if people like me keep thinking that everybody who voted for Trump is a racist or an asshole, then we’re fucked, because it’s simply not true. So this is one move toward something that might take a generation to change. I wanted to do something where that dialogue could begin.”

Ghosts of West Virginia centers on the Upper Big Branch coal mine explosion that killed twenty-nine men in that state in 2010, making it one of the worst mining disasters in American history. Investigations revealed hundreds of safety violations, as well as attempts to cover them up. The mine’s owners agreed to pay more than $200 million in criminal liabilities, and shut the mine down.

In ten deftly drawn, roughly eloquent, powerfully conveyed sonic portraits, Earle and his long-time band the Dukes explore the historical role of coal in rural communities. More than merely a question of jobs and income, mining has provided a sense of unity and meaning, patriotic pride and purpose. As sons followed their fathers and older brothers into the mines, generational bonds were forged. “You can’t just tell these people that you’re going to shut the coal mines without also telling them what you’re going to do to take care of them, to protect their lives,” Earle explains. To be sure, Earle’s politics have not changed. He believes in sustainable energy sources and ending fossil fuels. “But that doesn’t mean a thing in West Virginia,” he says. You can’t begin communicating with people unless you understand the texture of their lives, the realities that provide significance to their days. That is the entire point of Ghosts of West Virginia.

Earle started working on the album after being approached by Jessica Blank and Erik Jensen, a playwright team that would eventually create Coal Country, a theater piece about the Upper Big Branch disaster. Earle had previously worked with them on The Exonerated, an Off-Broadway play about wrongfully imprisoned people who ultimately proved their innocence and got released. Earle describes Blank and Jensen as creating “documentary theater,” and they received a commission from the Public Theater in New York. They interviewed the surviving West Virginia miners, along with the families of the miners who died, and created monologues for their characters using those words. Working closely with Oskar Eustis, the Public’s Artistic Director, they workshopped the songs and text for nearly four years. Earle functions as “a Greek chorus with a guitar,” in his words. He is on stage the entire play and, along with his song “The Mountain,” performs seven songs from Ghosts of West Virginia. “The actors don’t relate directly with the audience,” he explains. “I do. The actors don’t realize the audience is there. I do.” The songs provide personal, historical and social context for the testimony of the play’s characters, and, heard on their own, along with the album’s three additional songs, they provide a wrenchingly emotional portrait of a world that Earle knows well. “I felt that I could do it because so many of those people own Copperhead Road -- and I talk like this,” Earle says in the unreconstructed Texas drawl that has survived moves to Nashville and New York City, where he now lives.

Ghosts of West Virginia opens with “Heaven Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere,” a stark, a cappella spiritual that, in its sound and in its sense, captures the blend of faith and stoicism characteristic of mining communities. Without being explicit, “Union God and Country” nods to the deep union history of the West Virginia mines, a history that is being wiped out. “This was the most unionized place in America until the Nineties,” Earle points out. “Upper Big Branch was the first non-union mine in that area and it blew up and killed twenty-nine guys. That’s the deal.” “Devil Put the Coal in the Ground” is an expression of what Earle calls “a kind of hillbilly mindfulness” – a tough-minded recognition of the dangers of the mining life and the pride of doing such a demanding job in the face of those dangers. “The guy in that song is a miner and he’s being real about what he’s doing,” Earle says. On “John Henry Was a Steel Driving Man,” Earle, as so many have done before, takes the folkloric tale of the hammer-wielding hero and updates it for a contemporary world in which automation and union-busting have drained miners’ lives of so much of their potential and significance.

“Time Is Never On Our Side” was inspired by the four-day wait that four Upper Big Branch families endured because rescue teams found footprints in the mine that they believed might belong to miners they had not yet found. It turns out the footprints belonged to company managers who had entered the mine before the inspectors arrived, and failed to reveal that they had done so. The familial devastation wreaked by the mining disaster finds expression in “It’s About Blood,” in which, under a driving rhythm, Earle blazons the names of all the men who died in it. “If I Could See Your Face,” which closes Coal Country, is the only song that Earle does not sing. In the play, it’s sung by the actress Mary Bacon, while, on the album, that distinction goes to Eleanor Whitmore, who plays fiddle and mandolin in the Dukes. She delivers the ballad, a chronicle of memory, longing and loss, in a manner that is both feeling and plain-spoken, perfectly suited to its subject.

Despite its grim subject, “Black Lung” is rollicking and unsentimental, and it includes the verse that Earle describes as “the most important thing for me to say on this record”: “If I’d never been down in a coal mine,/I’da lived a lot longer/Hell, that ain’t a close call/But then again I’da never had anything/And half a life is better than nothin’ at all.” Those words were the last lyrics Earle wrote for the album, and they convey the reality of the lives that mining made possible for rural folk, regardless of the dangers.

“Fastest Man Alive” is a paean to Chuck Yeager, a West Virginia native who became a war hero and the first pilot to travel faster than the speed of sound. Earle treats him like a folk hero along the lines of John Henry and Davy Crockett (who, like Yeager, was a real person). Yeager’s life of risk in the sky offers a moving contrast to the miners facing danger underground, often unseen and unacknowledged. The album’s closing song, “The Mine,” was the first that Earle wrote, even though it was not included in Coal Country. It quietly gives voice to the hopes and fraternal bonds that a job in the mines once represented.

Earle and the Dukes recorded Ghosts of West Virginia at Electric Lady Studios, which Jimi Hendrix built in Greenwich Village, where Earle lives. That the album was mixed in mono lends it a sonic cohesion and punch, while losing none of the finely drawn delineation that the Dukes’ characteristically eloquent playing provides. More personally, however, the album is in mono because Earle has lost hearing in one ear and can no longer discern the separation that stereo is designed to produce. His partial deafness is not the result of exposure to loud volume that afflicts many musicians. He woke up one morning unable to hear in his right ear, and doctors have been unable to identify a cause. He’s been told a virus is likely the reason, but one doctor told him, “That’s what we say when we don’t know what the cause is.” As a result, Earle says, jokingly, “If I can’t hear the album in stereo, nobody else will either!”

The Dukes, too, suffered a major loss when, not long before the band went into the studio, bassist Kelley Looney, who had played with Earle for thirty years, passed away. Beyond the death of a longstanding partner in crime, Earle was faced with the prospect of finding someone who could share the telepathic musical communication so characteristic of the Dukes. Happily, Jeff Hill, who had previously worked with Earle and had most recently been part of the Chris Robinson Brotherhood, perfectly fit the bill. “Jeff stepped into the breach, but it was hard. It was really hard,” Earle says. Hill joined Whitmore, guitarist Chris Masterson, Ricky Jay Jackson on pedal steel, drummer Brad Pemberton and, of course, Earle on guitar and banjo. Their raw blend of country, rock and folk lifts the articulation of each song without the slightest hint of contrivance or pretension.

With Ghosts of West Virginia, Steve Earle has evoked a world as three-dimensional and dramatic as Coal Country, the play in which it found its origins, does on stage. That’s appropriate, because, as Earle says, “I came to New York to make music for theater, and it’s taken a long time. Theater is a powerful thing. It’s my favorite art form. It always has been. My ambition is to write an old-fashioned American musical. I’m a pretty good songwriter, and I just feel like I want to do that before I die.”

For now, however, there is Coal Country – and Ghosts of West Virginia. “I said I wanted to speak to people that didn’t necessarily vote the way that I did,” he says, “but that doesn’t mean we don’t have anything in common. We need to learn how to communicate with each other. My involvement in this project is my little contribution to that effort. And the way to do that – and to do it impeccably – is simply to honor those guys who died at Upper Big Branch.”

***

Steve Earle is one of the most acclaimed singer-songwriters of his generation, a worthy heir to Townes Van Zandt and Guy Clark, his two supreme musical mentors. Over the course of twenty studio albums, Earle has distinguished himself as a master storyteller, and his songs have been recorded by a vast array of artists, including Johnny Cash, Waylon Jennings, Joan Baez, Emmylou Harris, the Pretenders, and more. Earle’s 1986 debut album, Guitar Town, is now regarded as a classic of the Americana genre, and subsequent releases like The Revolution Starts...Now (2004), Washington Square Serenade (2007), and TOWNES (2009) all received Grammy Awards. Restlessly creative across artistic disciplines, Earle has published both a novel and a collection of short stories; produced albums for other artists; and acted in films, TV shows and on stage. He currently hosts a radio show for Sirius XM. In 2019, Earle appeared in the off-Broadway play Samara, for which he also wrote a score that The New York Times described as “exquisitely subliminal.” Each year, Earle organizes a benefit concert for the Keswell School, which his son John Henry attends and which provides educational programs for children and young adults with autism.

Contact Information

-

Management/Booking:

Management

Danny Goldberg & Jesse Bauer

Gold Village Entertainment

[email protected]

Publicity

Brady Brock

New West Records

[email protected]

Booking

North America:

Lance Roberts for UTA

[email protected]

Canada:

Nick Meinema for UTA

[email protected]

Europe:

Paul Fenn for Asgard

[email protected]

Australia & New Zealand:

Christian Bernhardt for UTA

[email protected]

Film & TV:

Brian Nossokoff for UTA

[email protected]

Media | Markets

- ▶ Buy My Music: http://hifi247.com/steve-earle.html

- ▶ Buy My Vinyl: http://hifi247.com/steve-earle.html

- ▶ Buy My Merch: http://hifi247.com/steve-earle.html

- ▶ Twitter: SteveEarle

- ▶ Instagram: steveearle

- ▶ Website: http://www.steveearle.com

- ▶ YouTube Channel: http://www.youtube.com/channel/UCPPWVL3JnDB1wfdviNoTPBg

- ▶ YouTube Music: http://music.youtube.com/channel/UCOFb6pfPUawqjZmIim-ykZQ

- ▶ Spotify: http://open.spotify.com/album/2XHFLRzTwQMQL8hrGeQoMC

- ▶ Spotify 2: http://open.spotify.com/album/15FbLxuzw8MuuIC1AOob6k

- ▶ Spotify 3: http://open.spotify.com/album/34VYeBzcQUwEPEDpH8WyMV

- ▶ Spotify 4: http://open.spotify.com/album/1CEAVKLVVaCoKyEoVVr8Bh

- ▶ Spotify 5: http://open.spotify.com/album/64DNjGvRmxv0GiDYqnrrqL

- ▶ Spotify 6: http://open.spotify.com/album/3JPaRHvPKF0iu7L9bTjJy4

Clips (more may be added)

-

Guitar Town with Steve Earle - Episode 1: 1890'S MARTIN 1-28

532 views

-

GUITAR TOWN WITH Steve Earle EP 2: 1870'S MARTIN 2-24

592 views

-

GUITAR TOWN WITH STEVE EARLE EP 3 1840 OR 41 MARTIN 3 17 copy

450 views

-

guitar town with steve earle episode 4 mp4

492 views

-

GUITAR TOWN WITH Steve Earle EP 5-1870'S AND 1931 MARTIN SIZE 0

528 views

-

GUITAR TOWN EP 6 1944 MARTIN 00 21

551 views

-

Steve Earle - Full performance (Live concert for The Current)

448 views

The Matrix is a small world network. Like stars coalescing into a galaxy, creators in the Matrix mathematically gravitate to proximity to all other creators in the Matrix, no matter how far apart in location, fame or society. This gravity is called "the small world phenomenon". Human society is a small world network, wherein over 8 billion human beings average 6 or fewer steps apart. Our brains contain small world networks...

![]() Wolfram MathWorld on the Small World Phenomenon

Wolfram MathWorld on the Small World Phenomenon

![]() Matemática Wolfram sobre o Fenômeno Mundo Pequeno

Matemática Wolfram sobre o Fenômeno Mundo Pequeno

"In a small world, great things are possible."

It's not which pill you take, it's which pathways you take. Pathways originating in the sprawling cultural matrix of Brazil: Indigenous, African, Sephardic and then Ashkenazic, European, Asian... Matrix Ground Zero is the Recôncavo, contouring the Bay of All Saints, earthly center of gravity for the disembarkation of enslaved human beings — and the sublimity they created — presided over by the ineffable Black Rome of Brazil: Salvador da Bahia.

("Black Rome" is an appellation per Caetano Veloso, son of the Recôncavo, via Mãe Aninha of Ilê Axé Opô Afonjá.)

"Dear Sparrow: I am thrilled to receive your email! Thank you for including me in this wonderful matrix."

—Susan Rogers: Personal recording engineer for Prince, inc. "Purple Rain", "Sign o' the Times", "Around the World in a Day"... Director of the Berklee Music Perception and Cognition Laboratory

"Thanks! It looks great!....I didn't write 'Cantaloupe Island' though...Herbie Hancock did! Great Page though, well done! best, Randy"

"We appreciate you including Kamasi in the matrix, Sparrow."

—Banch Abegaze: manager, Kamasi Washington

"This is super impressive work ! Congratulations ! Thanks for including me :)))"

—Clarice Assad: Pianist and composer with works performed by Yo Yo Ma and orchestras around the world

"Dear Sparrow, Many thanks for this – I am touched!"

—Julian Lloyd-Webber: UK's premier cellist; brother of Andrew Lloyd Webber (Evita, Jesus Christ Superstar, Cats, Phantom of the Opera...)

"Thanks, this is a brilliant idea!!"

—Alicia Svigals: World's premier klezmer violinist

Developed here in the Historic Center of Salvador da Bahia ↓ .

![]() Bule Bule (Assis Valente)

Bule Bule (Assis Valente)

"♫ The time has come for these bronzed people to show their value..."

Production: Betão Aguiar

MATRIX MODUS OPERANDI

Recommend somebody and you will appear on that person's page. Somebody recommends you and they will appear on your page.

Both pulled by the inexorable mathematical gravity of the small world phenomenon to within range of everybody inside.

And by logical extension, to within range of all humanity outside as well.

MATRIX (PARDAL)

I'm Pardal here in Brazil (that's "Sparrow" in English). The deep roots of this project are in Manhattan, where Allen Klein (managed the Beatles and The Rolling Stones) called me about royalties for the estate of Sam Cooke... where Jerry Ragovoy (co-wrote Time is On My Side, sung by the Stones; Piece of My Heart, Janis Joplin of course; and Pata Pata, sung by the great Miriam Makeba) called me looking for unpaid royalties... where I did contract and licensing for Carlinhos Brown's participation on Bahia Black with Wayne Shorter and Herbie Hancock...

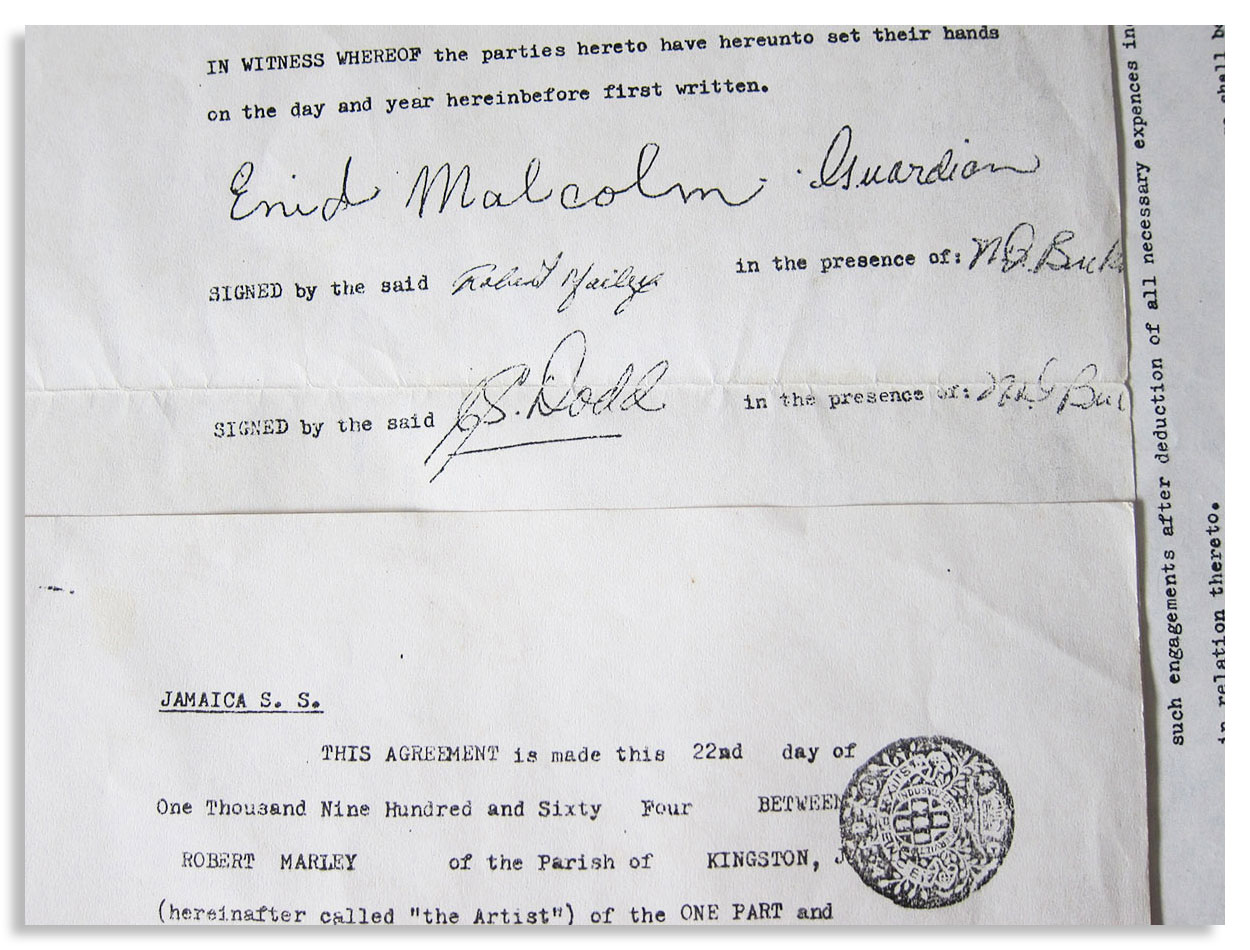

...where I rescued unpaid royalties for Aretha Franklin (from Atlantic Records), Barbra Streisand (from CBS Records), Led Zeppelin, Mongo Santamaria, Gilberto Gil, Astrud Gilberto, Airto Moreira, Jim Hall, Wah Wah Watson (Melvin Ragin), Ray Barretto, Philip Glass, Clement "Sir Coxsone" Dodd for his interest in Bob Marley compositions, Cat Stevens/Yusuf Islam and others...

...where I worked with Earl "Speedo" Carroll of the Cadillacs (who went from doo-wopping as a kid on Harlem streetcorners to top of the charts to working as a janitor at P.S. 87 in Manhattan without ever losing what it was that made him special in the first place), and with Jake and Zeke Carey of The Flamingos (I Only Have Eyes for You)... stuff like that.

Yeah this is Bob's first record contract, made with Clement "Sir Coxsone" Dodd of Studio One and co-signed by his aunt because he was under 21. I took it to Black Rock to argue with CBS' lawyers about the royalties they didn't want to pay (they paid).

MATRIX MUSICAL

I built the Matrix below (I'm below left, with David Dye & Kim Junod for U.S. National Public Radio) among some of the world's most powerfully moving music, some of it made by people barely known beyond village borders. Or in the case of Sodré, his anthem A MASSA — a paean to Brazil's poor ("our pain is the pain of a timid boy, a calf stepped on...") — having blasted from every radio between the Amazon and Brazil's industrial south, before he was silenced. The Matrix started with Sodré, with João do Boi, with Roberto Mendes, with Bule Bule, with Roque Ferreira... music rooted in the sugarcane plantations of Bahia. Hence our logo (a cane cutter).

A Massa (do povo carente) / The Masses (of people in need)

-

Add to my PlaylistA Massa - Raymundo Sodré (7,093 plays)

-

Add to my PlaylistSina de Cantador - Raymundo So... (6,909 plays)

-

Add to my PlaylistMagnetismo - Raymundo Sodré ... (6,353 plays)

-

Add to my PlaylistSacando a Cana - Raymundo Sodr... (5,957 plays)

-

Add to my PlaylistMêrêrê - Raymundo Sodré (5,465 plays)

-

Add to my PlaylistJardim do Amor - Raymundo Sodr... (4,677 plays)

-

Add to my PlaylistDebaixo do Céu - Raymundo Sodr... (4,151 plays)

-

Add to my PlaylistDesejo de Amar - Raymundo Sodr... (3,861 plays)

-

Add to my PlaylistOração pra Yá Oxum - Raymundo ... (3,741 plays)

-

Add to my PlaylistYá África - Raymundo Sodré (3,509 plays)

-

Add to my PlaylistMeu Rio, Cadê o Papel - Raymun... (3,177 plays)

-

Add to my PlaylistCasa de Trois - Raymundo Sodré... (2,896 plays)

-

Add to my PlaylistMulher é Laço que Prende o Coração do Vaqueiro - R... (2,556 plays)